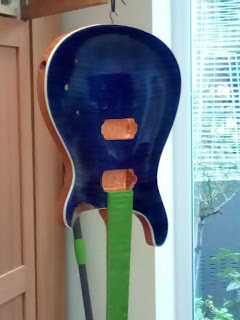

Following some advice I received on an internet group of guitar builders, I’ve given the body – front, back and sides – three thorough buffings with Meguiar’s compound and the difference is stunning, even if I say so myself. Although the top still has the surface texture of the flame element of the veneer and the sides and back (especially) retain the grain of the mahogany, nevertheless the gloss is quite mirror-like. Although it’s clearly not professional I think I’ve about exhausted the limits of my ability and it’s time to start adding the hardware and electronics.

Today had to be a 'plus' because when I came to fit the machine heads (tuning gears) I discovered one of them didn't have a hole in the shaft in which to insert the string. Almost in disbelief, I contacted the kit supplier and, once again, they stepped up to save the situation. By overnight courier, they delivered a new set of machine heads so that I could do the basic completion of the guitar in time to make a sort of presentation to my grandson for Christmas. I use that term because his present is actually a ukulele on which to have his first lessons since, at 5, his fingers don't extend to any sensible guitar. The home build is a goal for him to achieve.

Although I detect a small change in the neck/body joint the guitar has fulfilled most of my hopes by not folding into an unwanted 'travel guitar'. I used the supplied strings which, although they're unbranded and unpackaged, seem to be very lightweight and are quite adequate for the present purpose.

The instrument seems to be quite playable with a very straight fretboard and a very fast action. That aspect pleases me greatly. I'm somewhat less enthusiastic about the pickups but I've only had a few minutes playing through the amplifier to make sure that they both work and some post-Christmas fettling will probably improve things.

Would I do it again? Yes, in fact, I've ordered a short-scale bass guitar kit for delivery in the New Year. I'd have preferred an ash-bodied kit but they're no longer available so mahogany will have to do.

Would I use UK Music Supplies and their Coban brand? Again yes. The quality of the wood, especially the neck and the fretboard are the clincher, that and the company's attitude to its customers. As far as that's concerned I can do no better than repeat her an entry in my main blog which sums up my whole experience.

One of life's truths is that we all make mistakes. Happily, most of them are insignificant or can be corrected but even then, there are degrees of errors. At their heart, they're all human failings but even so when the person is acting for a company it's the company's reputation that invariably suffers. Since the ability or even propensity to make mistakes is universal, it's not practical or realistic to simply stop using or supporting the company that's dropped a clanger. Instead, I've come to apply another measure; how does the business react when they've made a mistake?

I've recently encountered two instances (both on e-Bay) in which the individual responsible for the mistake completely failed to act properly. As a result, their reputation and standing have suffered and in one case they were financially penalised by the portal as well.

In contrast, a company from which I bought a kit from which to build an electric guitar (a Christmas present I was allowed to start before the actual day as a lockdown therapy). In total, the company has made three mistakes yet, even as I write, the manner in which the company – really the people working for the company – has responded has not led me to rule out buying from them again.

Initially, the kit was supplied with a one-piece bridge/tail unit suitable for another style of guitar. The cavity in the body has to match the design of the unit so it was simply not possible to use the wrong part. I sent the incorrect parts back at once and the company despatched the correct bridge and stoptail parts. Unfortunately due to the prevailing season and national state of health, these didn't arrive so I complained. The company responded by sending another set of bits. Coincidentally the two consignments (sent at different service speeds although the slower was also further delayed en route) arrived in the same post.

However, when I came to assemble the hardware elements of the guitar I discovered that although I'd counted the number of tuning devices supplied – one for each of the six strings – I'd failed to notice that one had no hole through which the string could be pushed to fasten to the tuning head. Not only is this unusual – the company entirely plausibly claimed it to be the first time such an error had occurred – but it makes one wonder how such a mistake could even occur.

The guitar might have been a Christmas present which would have been spoilt by the error but the action of the supplier – sending a replacement part by overnight carrier – has left me as satisfied with the company as I would have been had the errors never occurred.

In other words, my measure of the company as a supplier isn't reflected in the quality of its product but by the way it has handled its mistakes. Have I always felt this way? Probably not. More relevantly, did others treat me like that when I made my mistakes? I hope so.